|

The Lorenz and the Colossus

Alan Turing returned from USA to Bletchley Park in March 1943. While the Enigma decipherment continued on an industrial scale, the most innovative work concerned the

top-level strategic German messages which were enciphered on the completely different, teleprinter-based Lorenz cipher machine.

Turing's involvement in this work has already been mentioned on the previous Scrapbook page.

|

|

The Lorenz produced messages which at Bletchley Park were referred to as 'Tunny' ciphertext. These were attacked with increasing success after a young mathematician, W. T. Tutte, brilliantly exploited a dramatic German transmission error of 30 August 1941 and so discovered the basic structure of the cipher machine (which was, in fact, never captured.)

See the description by Tony Sale of the Lorenz machine. See also the overall

NSA survey of German cipher machines.

|

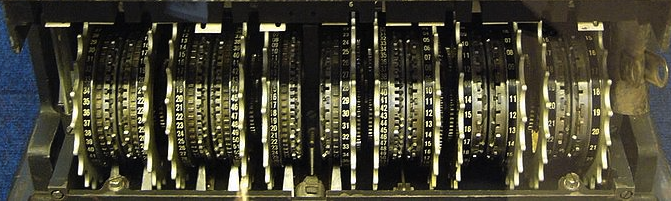

The rotors of the Lorenz machine, whose structure was deduced entirely by logical analysis at Bletchley Park. |

|

Bill Tutte gave a very modest account of this work, Fish and I. It includes the specific method (called 'Turingismus') for breaking Lorenz ciphers that Alan Turing worked out after Tutte's breakthrough.

Turing's contribution to the 'Tunny' problem also emerges in two wartime reports now available on Tony Sale's site. These are the History of the Newmanry and the Special Report on Fish.

The Newmanry report is in fact just part of the General Report on Tunny, available in transcription on Graham Ellsbury's website.

This report shows very clearly the debt to Turing's statistical theory as originally developed for the attack on naval Enigma.

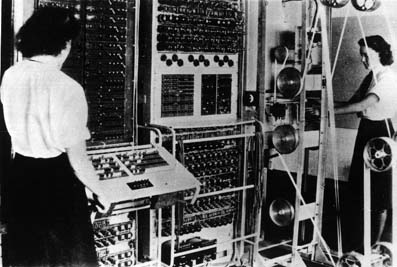

The 'Newmanry' took its name from Max Newman (the same Cambridge mathematician who had introduced Turing to logic in 1935) who took charge of this section of Bletchley Park work in 1942. Under his direction, new statistical methods were automated by building new machines with the first large-scale use of electronic switching. Later versions of the Bombe used a few electronic valves for fast switching, but the Colossus, started in 1943 for work on 'Fish', used thousands. Tony Sale has given an illustrated description of his Rebuilding of the Colossus on his site. There is an on-line Colossus simulator on the Virtual Bletchley Park pages.

The Colossus project, together with many other projects of reconstruction, has been taken over by the National Museum of Computing, and is open to the public. See the page on the

Colossus rebuild, which is still in progress.

| |

Alan Turing did not become the chief figure in the Tunny work, and in particular did not design or build the Colossus, as is often incorrectly stated. The Colossus was not applied to Enigma ciphers! However, it depended on the statistical theory that Alan Turing had developed for breaking the naval Enigma.

It was important that Turing knew all about the success of the Colossus, because this was the first large-scale application of digital electronics, and showed that this technology was reliable and practical. Turing's acquaintance with this work allowed him to plan with confidence for the computer of the future.

|

The electronic Colossus, working in time for D-Day,

6 June 1944.

|

What if...

Here is a transcript of a much-quoted 1993

talk by Sir Harry Hinsley on the significance of work done at Bletchley Park. During the Second World War Hinsley worked on interpreting the naval messages that were decrypted by Turing's group. In the 1970s he become the official historian of the whole operation.

Hinsley went into the question of what would have happened if the Enigma had not been broken. He speaks of an invasion of Europe taking place in 1946 or 1947: a mere deferment of the inevitable. But a continuation of the war after 1945 would have been very different. The Allies were all prepared to infect Germany with anthrax, and after July 1945, American atomic bombs would have become available at the rate of one a month, presumably annihilating German cities or U-boat bases one by one. Would these measures have induced German surrender, or led to protracted guerrilla war? Would there have been chemical or biological retaliation on Britain? Where would this have left the Soviet Union?

|

Secret speech (1)

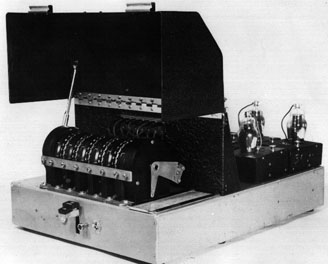

After August 1944, with the invasion of Europe secure, Alan Turing spent more time with his hands on electronics, preparing himself for the design of an electronic computer. He did this at the MI6 base at Hanslope Park, Buckinghamshire. With the assistance of Donald Bayley, a young electronic engineer, he built an advanced speech scrambler of his own elegant design.

|

They called it the Delilah.

This was at the suggestion of the young Cambridge mathematician Robin Gandy,

who was also working there.

After 1948 Robin Gandy became Alan Turing's student, colleague and close friend. |

Secret Speech (2)

Alan Turing was particular open about his being gay while working with Donald Bayley. The young engineer was amazed at meeting someone who was open and 'almost proud' of it. He also told me how in 1944 he left this as a private matter, but that if such a thing had happened after 1948 when new 'security' rules came into force, he would have had to report it. Donald Bayley spoke further of this on the television programme made in 1992, The Strange Life and Death of Dr Turing, YouTube version here, and said how by 1952 homosexuality was 'beyond the pale' and disqualified anyone from secret work.

Alan Turing's colleague Jack Good, however, said on the same television programme that if the security authorities had known about Alan Turing's homosexuality from the beginning, 'we might have lost the war.'

The author Arthur C. Clarke made a similar claim in a foreword to a book on Artificial Intelligence: 'How ironic that Alan Turing, who perhaps contributed more than any other individual to the Allied victory, would never have been allowed into Bletchley under normal security regulations.'

In a subsequent interview, Donald Michie pointed out to I. J. Good that various other gay men at the Bletchley Park establishment were quite open with him, and thus confirming that such 'security' vetting only started after the Second World War.

|

|

Alan Turing enjoyed a pleasant life at the secret Hanslope base, in those innocent pre-Vetting days. He delighted in going running, and finding mushrooms in the countryside. Once he found the deadly Amanita Phalloides or Death Cap.

|  |

|

The secret mushroom cloud

The atomic bomb was soon to be open knowledge. This other application of leading mathematics and science, equally central to the Second World War and its aftermath, remained a closed book.

Everything about Bletchley Park had been borrowed from twenty years ahead of its time. The mathematical methods, the electronic technology, the informal organisation and breaking of barriers, the social and sexual liberalism, giving women and young people a vital place. To defeat Nazi Germany, the future was borrowed — though hardly anyone knew what had happened. Alan Turing was one of a tiny few with any understanding of the overall picture, and everyone maintained total secrecy about it for thirty years.

|

The image of fireworks at Bletchley Park

is used by Sir Eduardo Paolozzi in the last of his

Turing Collection of screen-prints

See my talk about this print and its images.

|

The door out of Bletchley Park |

Alan Turing at the end of the war

Of all those who worked at Bletchley Park, the closest to Alan Turing's mathematical work was probably Jack Good. Here is Good's closing comment, from the summary he wrote in Codebreakers, about the work they did: ...the success of our efforts during the war, and the feeling that we were helping substantially, and perhaps critically, to save much of the world (including Germany) from heinous tyranny, was a hard act to follow.

A hard act to follow... but in 1945 Alan Turing was very confident about his future plans. His hands-on work on electronics was practice for the construction of a Universal Turing Machine — the computer of the future.

|

Continue to the next Scrapbook page.

|

|

|